Congratulations – you’ve run your first geo experiment (or two!). But for many brands, this is the first time you've measured incrementality, and results may look… a little different from what you're used to seeing in ad platforms.

A couple things to think about as you evaluate results:

- How does your iROAS or CPIA compare to other tests you've run?

- How does it compare to what you need in order to be profitable?

- Are you willing to take on inefficient spend if it means keeping the top of funnel healthy?

Let’s look at a common hypothetical.

My results aren't what I expected. Why?

First of all, you're not alone – it's not uncommon to see iROAS <1. So what should you do? How should you think about low estimates and how to put them into context for decision-making?

1. These are short-term efficiencies, not cumulative efficiencies

Not all purchases are impulse purchases – buying decisions often take time, especially for purchases with a higher average order value (AOV). When an impression is served, customers who may eventually convert might not do it right away – buyers often need time to consider, comparison shop, or wait for a convenient time.

The kinds of businesses for which this may be relevant:

- High ticket

- Delayed gratification

- High time or trust investment

- Durable products

The kinds of businesses for which this may not be relevant:

- Low ticket

- On-demand gratification

- Little time or trust investment

- Consumable products

2. These are average efficiencies, not marginal efficiencies

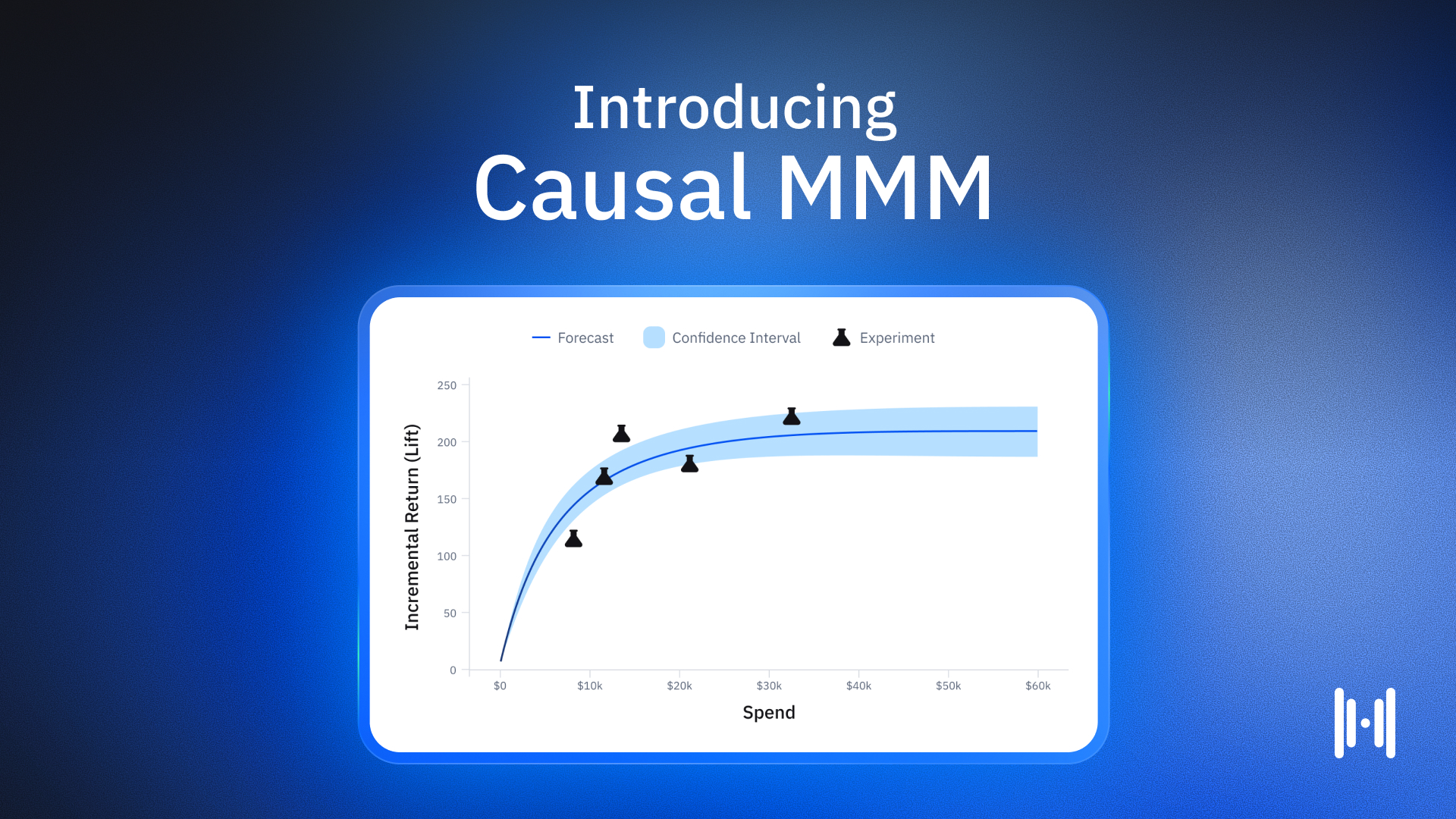

The results we observe from experiments are essentially estimates of average effects. This is a crucial factor to consider when interpreting results, as average effects are distinct from marginal effects. It's important to remember that if an average effect doesn't appear profitable at a high level of investment, it doesn't necessarily imply global unprofitability (more on this below). Given the assumption of a diminishing marginal return curve, it's possible that the effects could yield profitability at lower spend levels.

It's worth noting the different types of tests that can be conducted: reporting tests and optimization tests. Reporting tests typically involve 2-cell designs with holdouts and are primarily aimed at identifying average effects. They provide a snapshot of the overall performance but don't offer much insight into how changes in spend levels might affect outcomes. In contrast, optimization tests can involve 2- or 3- cell tests across varying spend levels, allowing for the tracing of the diminishing return curve. These tests are designed to identify the optimal level of spending by assessing the incremental impact of each unit of additional spend. They provide a more nuanced view of the data, helping to inform decisions about how to adjust spend levels to maximize return.

3. If you sell in channels outside of DTC — but only measure DTC — you may be missing the full picture

Customers don't always purchase where your marketing tells them to. If you sell in more than one channel (e.g. DTC, retail, Amazon, etc.) but you only measure DTC, you might be under-valuing impact.

Haus can ingest Amazon and retail data to report total lift across all sales channels for every experiment you run — so that you can better understand whether your spend is shifting users from one sales channel to another, or driving incremental sales you previously could not observe. (Check out how our partnership with Crisp makes this super efficient for CPG brands.)

How should I think about test results that are incremental but not profitable?

If you’re still trying to wrap your head around what to do when test results are incremental but not profitable, Haus’ Head of Strategy Olivia Kory and Measurement Strategy Lead Nick Doren have a great ~9 minute explainer on this exact situation. Ultimately, Nick likes to remind brands that incrementality is relative to spend – and that organic contributions to the business shouldn’t be forgotten. “You actually have a bit of leeway on a paid acquisition standpoint to ladder into your overall goals as a business, “he says.

Olivia echoes the sentiment and challenges brands to think about it this way: “If your CPIA [cost per incremental acquisition] comes up and it’s not profitable based on your goals, but you are still spending profitably on a blended basis, can you spend slightly less efficiently than you’d like in pursuit of growth?

Knowing that you’re where you need to be from a top line, moving money from less incremental pockets to more incremental pockets, you will see that show up in terms of improved MER [marketing efficiency ratio].”

A decision-making framework to help you act based on incrementality test results

If you’re doing a lot of head-nodding as you skim this, you’re not alone. Fortunately, Haus’ Measurement Strategy Manager, Stephen Barston, developed a handy framework to help orient brands towards appropriate action depending on where an experiment’s results fall on an axis of Lift Percentage against Actualized CPIA Relative to Your Target.

At the end of the day, it’s a learning process. Developing a culture of experimentation takes time, and all the incrementality interest in the world won’t move the needle if you don’t have a clear path to action. That’s why we’re here – so you can make smarter, more profitable business decisions with confidence.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.avif)

.png)

.avif)